Welcome to part three of our macronutrient series! We’ve covered fats and carbs, and now it’s time to take a look at the third and final macronutrient: protein. In this simple guide to protein, you’ll learn about:

- The structure of protein

- Complete vs. incomplete proteins

- How you digest protein

- Denatured protein (and whether it’s good or bad)

- Protein’s many benefits, and how your body uses it

- Good sources of protein

Protein gets a lot of credit for building stronger muscles. Rightly so – it’s fundamental in muscle repair and growth. But protein’s role in your body goes far beyond getting you jacked. You can also use it to enhance metabolism, fat loss, mood, brain function, hormonal balance, and more.

Let’s start with the basics. What is protein, exactly?

Protein structure, amino acids, and “complete” proteins

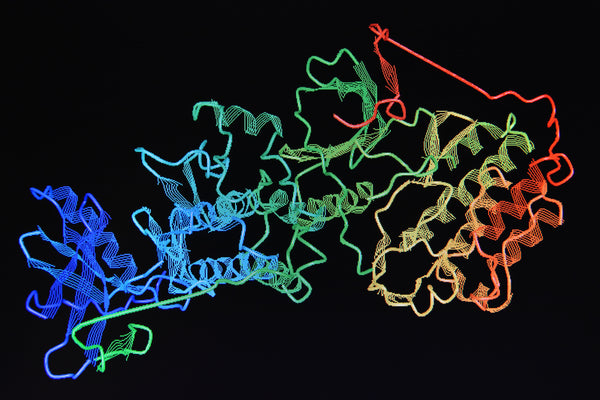

Proteins look kind of crazy. Where fats and carbs are usually nice neat molecules, proteins are complicated folded structures. Have a look for yourself:

Full disclosure: proteins are rarely this rainbow-colored in real life.

Protein is made up building blocks called amino acids – little bundles of nitrogen, hydrogen, carbon, oxygen, and sulfur. Most proteins contain 300+ amino acids, all bound together in strings.

The different amino acids in a protein determine what that protein does for you. Whey protein, for example, contains a lot of amino acids that contribute to muscle growth, while collagen protein has amino acids that help with skin elasticity and decreasing wrinkles.

There are 20 different amino acids that make up proteins. Of those, 9 are essential amino acids – your body won’t produce them on its own, so you have to get them from diet. The most convenient way to get the amino acids you need is by eating complete proteins. Complete proteins contain all 9 essential amino acids in a ratio that’s useful for your body.

Does that mean you have to worry about incomplete proteins?

It depends. All animal proteins – red meat, poultry, pork, eggs, seafood, and dairy – are complete proteins, so as long as you regularly eat meat, eggs, or high-protein dairy like cheese or yogurt, you should be set.

If you’re vegetarian or vegan, you’ll want to be a little more mindful of your protein sources. Most plant proteins are incomplete, which means you shouldn’t rely entirely on a single food for protein. There are a couple exceptions, though: two complete plant proteins are quinoa and buckwheat (both of which are gluten-free, by the way).

Exceptions aside, the rule of thumb for vegetarians and vegans is to combine legumes – beans, lentils, peas, peanuts – with whole grains – rice, oats, barley, and so on. The complementary amino acids in legumes and whole grains usually add up to a complete protein.

Many cultures figured this combo out a long time ago. It’s why you see legumes and grains paired together as staple foods in so many different cuisines: for example, rice and beans in South America and Mexico, rice and daal (lentils) in India, and rice and soy in Japan and China. Complete protein is fundamental to a healthy diet.

How you digest protein

You start breaking protein down in your stomach.

- It all begins with pepsin, an enzyme that breaks apart the bonds holding protein together. Proteins are hundreds of amino acids, linked together by peptide bonds. In your stomach, pepsin breaks apart those peptide bonds, cutting proteins down into shorter chains of amino acids.

- Next, these smaller pieces of protein go to your small intestine, where three more enzymes get to work on them. Trypsin, chymotrypsin, and carboxypeptidase start hydrolyzing the protein fragments – they bring water (hydro-lize) to the scene and use it to break the fragments into smaller and smaller pieces, and eventually single amino acids.

- The single amino acids go through the lining of your small intestine and into your bloodstream.

- Branched-chain amino acids (BCAAs) go to your muscles, to help repair and grow muscle fibers [1]. BCAAs are three of the nine essential amino acids: leucine, isoleucine, and valine.

- All other amino acids make their way to your liver. Your liver can reconfigure them into amino acids you need, break them down into glucose for fuel, ship them out to other parts of your body (your brain, for example), or turn them into blood-clotting proteins and plasma for your blood.

Is denatured protein good or bad?

You may have read that denatured protein is bad for you, and that you want to avoid denaturing your protein as much as possible.

That’s not automatically true. Denaturing sounds awful, but all it means is breaking protein down from its original form. You denature proteins when you digest them, and in some cases, buying denatured (think pre-digested) protein can help you absorb the amino acids better.

A good example is hydrolyzed collagen. Intact collagen is tough to digest and you don’t end up absorbing all of it. Hydrolyzed collagen has already been broken down into peptides, saving your body a couple steps in the digestive process. That makes hydrolyzed collagen more bioavailable and easier on your digestion.

On the other hand, there are types of denaturing you don’t want. Searing/charring protein on high heat destroys parts of it and creates carcinogens. That’s not great (although the occasional nicely seared steak is probably worth the carcinogens).

So don’t let the word “denatured” scare you right off the bat. It’s not automatically a bad thing.

Now let’s take a look at how your body uses protein and amino acids.

Fat loss, muscle, and mood: the many ways you use protein

Protein is unique as a macronutrient. While you mostly turn fats and carbs into fuel, your body rarely relies on protein as an energy source. Instead, amino acids and proteins end up in all kinds of places, doing everything from building muscle to sharpening brain function to acting as hormones. Here are a few examples of what you do with protein (and why it’s so important to get enough of it):

- Muscle synthesis. When you exercise, you’re quite literally tearing apart your muscles. The soreness you feel post-workout is the result of damaged muscle fibers. It’s the good kind of damage, though: amino acids – particularly the BCAAs you read about in the last section – come in and help repair/rebuild your muscles stronger than they were before you exercised. Protein, and BCAAs in particular, can speed up recovery and enhance muscle growth [2]. That’s part of why we added grass-fed whey protein to Ample original and Ample K; whey is especially rich in muscle-repairing BCAAs.

- Hormone balance. A lot of important hormones are made up of amino acids. Notable examples are insulin (regulates metabolism and hunger), human growth hormone (stimulates bone and muscle repair and growth), oxytocin (promotes empathy and bonding with those around you), and the hunger hormones leptin and cholecystokinin (to tell you when you’re hungry or full, respectively) [3].

- Fat loss and satiety. Protein is the most filling macronutrient [4]. No surprise, then, that a moderate-to-high-protein diet leads to gradual fat loss over time [5,6].

- Stronger skin and joints. The amino acids glycine, proline, and hydroxyproline are essential parts of collagen and elastin, the components of skin and joints that keep them moisturized and give them elasticity [7,8]. Animal collagen is rich in glycine, proline, and hydroxyproline, which is why Ample original contains grass-fed bovine collagen.

- Mood and brain function. Amino acids are the building blocks to several important neurotransmitters – chemicals that help your brain run smoothly. One example is tryptophan, which turns into serotonin. Serotonin regulates mood, which could explain why a diet with plentiful tryptophan improves overall mood and decreases symptoms of depression [9]. Tyrosine, another amino acid, turns into dopamine, the neurotransmitter that affects motivation and pleasure. Glutamate, which is itself an amino acid, is the major excitatory neurotransmitter in your brain.

How much protein should you eat?

Great question. Aim for a minimum of 0.5 grams of protein per pound that you weigh (0.5g/lb protein), to supply your system with plenty of amino acids and prevent muscle loss [10]. A 200-lb person, for example, would want 100 grams of protein a day.

Exercise drives your protein requirements up because your muscles are hungry for amino acids to repair. If you work out regularly, go for closer to 0.8g/lb bodyweight (e.g. 160 grams for a 200-lb person) [11]. Definitely aim for this number if you’re looking to put on muscle.

Good sources of protein

Here are some of our favorite high-quality protein sources.

Animal protein sources:

Animal protein sources:

- Grass-fed beef and lamb

- Chicken (preferably pasture-raised)

- Eggs (again, preferably pasture-raised)

- Grass-fed cheese

- Wild-caught fish

- Grass-fed whey

- Grass-fed collagen

Complete plant protein sources:

- Quinoa

- Buckwheat

- Rice and beans

- Rice and lentils

- Eggs (not vegan)

- Pea protein

- Brown rice protein

- Hemp protein

Have you noticed benefits from adding more protein to your diet? What are your favorite protein sources (we’re especially curious about you vegetarians and vegans out there)? Let us know in the comments. Thanks for reading!

The post A Simple Guide To Protein appeared first on Ample.

My favorite protein would be Salmon, chicken, all fish canned and caught. Eggs, nuts.

Thank you for all that information…I needed all that! Keep up the good work!